Now Streaming: 'Asteroid City' Makes a Weirdly Good Double Feature with 'Oppenheimer'

Wes Anderson's latest explores glibness and gadgetry in the Atomic Age, along with a wildly unnecessary framing device.

I first saw Asteroid City the week it came out, while I was still trying to figure out what this newsletter should be. I meant to review it and I thought that meant seeing it as soon as possible. I tried to squeeze it into regular weeknight rotation, after putting a toddler to bed and a few drinks at dinner.

That didn’t work out so well. I felt sleepy and disassociated, left wondering whether my failure to lose myself in the movie was my fault or the movie’s. Either way it left me cold, in a way that Wes Anderson movies rarely do. Do you ever wonder if you’ve lost the ability to watch movies without a 10-second rewind button?

While I was busy pondering the age old question of “is movie bad or am I just old?” everyone else seemed to be hailing it as Wes Anderson’s best film in years (which, to be fair, critics mostly do as a reflex these days, promotion of the theatrical experience having become their primary objective). And so I sat it out, my only deadline having been self-imposed anyway.

Now that Asteroid City is streaming on Peacock, I decided to revisit it, fully sober and with all the attention span band-aids streming can provide, not to mention subtitles. Critics rarely give films we’ve dismissed such a retry.

Upon second viewing, I certainly enjoyed the experience more, as often happens once you’ve freed yourself from the burden of trying to “get” it. And yet it also brought into focus what kept me from loving it the first time around.

Asteroid City feels like a lovely proof of concept for the brilliant little movie it could be, unfortunately cocooned inside a framing device that at best feels like an unnecessary apology for it, and at worst an attempt at padding — additional construction standing in for complete articulation.

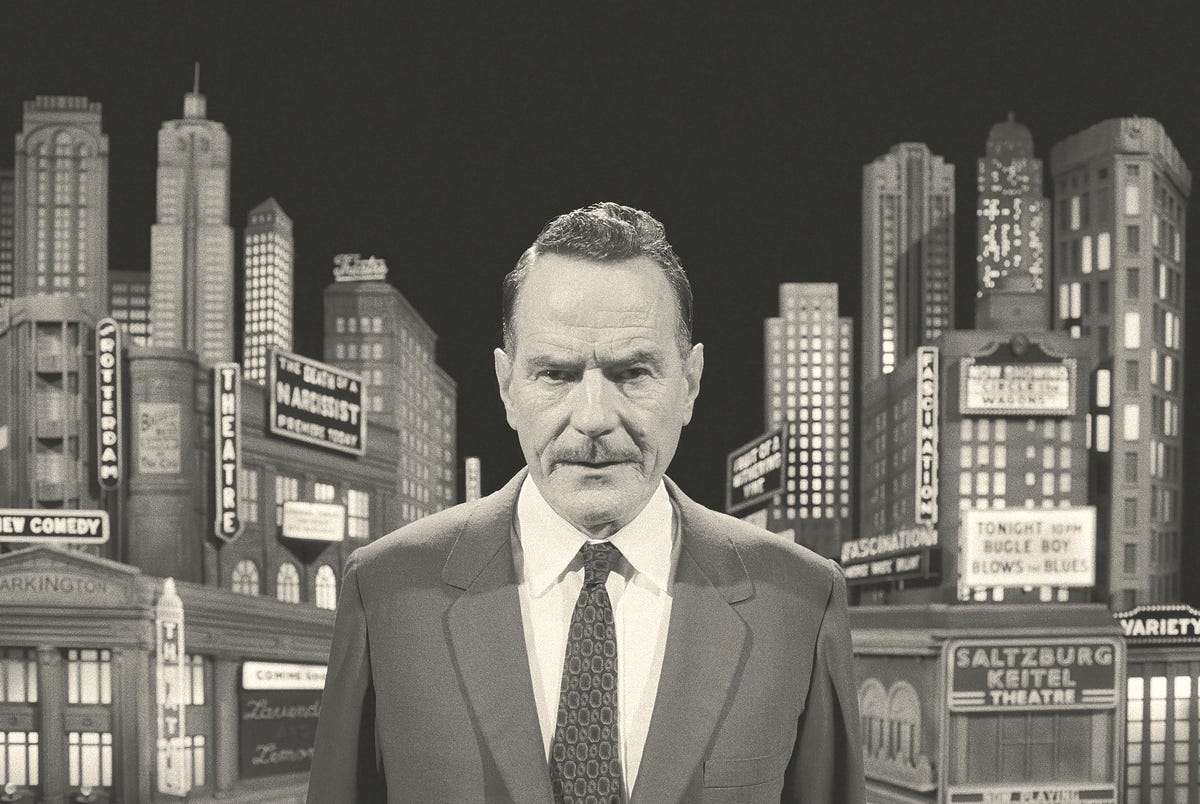

Asteroid City opens with what New Yorker critic Richard Brody calls “an ingenious setup” and “a giddy confection of metafictional whimsy,” — Bryan Cranston playing the host of a 1950s-style black-and-white television show, which he tells us is going to be a story about the creation and production of a “nonexistent” play called “Asteroid City.” We zoom past Cranston, into a shot of playwright Conrad Earp (both fictional and nonexistent) typing away at the script for this play we’re about to watch.

After a dissolve to the title sequence, the framing device falls away and the play-within-a-show becomes the movie we’re watching: a story about a group of folks who come together for a convention of Junior Stargazers and Space Cadets in the fictional western town of Asteroid City (population 87). Essentially, a group of precocious child prodigies and their curmudgeonly, emotionally wounded parents: Wes Anderson’s two favorite types of characters.

These include: Jason Schwartzman’s Augie Steenbeck, a war photographer accompanying his prodigy son and girl triplets, who he hasn’t yet told of their mother’s death three weeks ago; Scarlett Johansson’s Midge Campbell, a famous actress preparing for her next role as a suicidal housewife, accompanying her a genius daughter; Jeffrey Wright’s Grif Gibson, a gruff yet grandiose four-star general, there to present the scholarship for the winning Junior Stargazer; along with a handful of others, like the Motel manager played by Steve Carell (selling useless plots of land and perfecting vending machine tech) and a cowboy singer played by Rupert Friend, a new and weirdly perfect face for Wes Anderson.

The setting (the small town American West, circa 1955) naturally allows Anderson to indulge in his favorite mid-century modern clothes and styles. It’s fun to ponder which came first, Wes Anderson’s idea for this movie or the safari suit Jason Schwartzman wears in it. Inasmuch as it’s his perfect excuse to shoot beehive hairdos and cowboy cap guns, Anderson also takes the opportunity, arguably as never before, to explore the collective psyche of the society that produced them.

One of its very first shots is of the stylized, unapologetically hyperreal train (think the Beatles’ yellow submarine) that brings the town its supplies: grapefruit, pecans, and avocados, all matter-of-factly labeled, like Wile E. Coyote’s Acme devices. Pointedly ensconced among them, at once out of place and perfectly apt, sits a nuclear warhead. The implication is clear: the society that produced all this abundance, the fertile ground from which spring all the clunky toys and retro-futurist fashion Anderson clearly so loves, is also a violent and paranoid one, prepared to instantly vaporize anyone who threatens it.

Even the central event of the film — this convention of Junior Stargazers and Space Cadets — is at once an innocent playground for precocious geniuses (presumably like Anderson himself), and a paranoid government’s attempt to coopt them into the cause of “national defense.” One of its best scenes is General Grif’s introductory speech for the event, which he uses as a sort of trial run for his bombastic Cold Warrior’s memoir.

With great ceremony, he orates at breakneck speed:

My father went off to fight in the war to end all wars. It didn’t, and what was left of him came back in a pine box with a flag on top. End of Chapter Two. Next, I went to officer school, and 20 years passed at the speed of a dream. A wife, a son, a daughter, a poodle. Chapter Three. Another war. Arms and legs blown off like popcorn, eyeballs gouged out, figuratively and literally. The men put on shows under the palm fronds dressed as women in hula skirts.

This is arguably further than Anderson has gone before in exploring what drives the gadgets, gizmos, uniforms, and supplies lists he seems to love putting into every movie (along with vain authority figures). The general is one of the guys in charge of creating this way of life, which he did through blood, guts, and repressed homoerotic urges, carrying the scars of an abusive childhood. That it’s all played for successful comedy (in a movie that otherwise only gave me a couple mild chuckles) distinguishes it as of Anderson’s best comedic monologues.

These proceedings are eventually interrupted by the appearance of an alien (depicted with transparent artifice, a la the Jaguar Shark in The Life Aquatic), who descends his spaceship and absconds with the town’s asteroid — inspiring the military men to put the entire town on lockdown. The story then takes place in this odd little interlude outside the character’s normal lives, in which they dream, ponder, reflect and fall in love — the widowed war photographer with the movie star who never gets to indulge her true talents as a comedienne; the cowboy singer with the school teacher; two awkward nerd kids with each other; Tilda Swinton’s astronomer with a kid she perceives as her younger self (platonic love affairs between teacher and student being another of Anderson’s pet topics).

This a wonderful movie, a perfect little Wes Andersonian corollary to Oppenheimer, reveling in all manner of detail the characters themselves gloss over as their mundane. If Oppenheimer is a biopic about the haunted father of this whole paranoid-but-absurdly-wealthy society, Asteroid City is a technicolor daydream of how eerily pleasant it was to experience first-hand, but for those occasional eruptions of well-founded paranoia and existential dread (I’d also recommend here The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, Bill Bryson’s charming memoir/portrait of post-War American prosperity).

And yet Anderson insists on breaking in, again and again, with his framing device, with vignettes about the “actors” playing the characters in this “play,” wondering what it all means and shattering the fourth wall (or however many walls there are). Did you know art isn’t actually real, but it can sometimes feel real? More real than reality, even? (Frankly, Tropic Thunder did it better).

Jason Schwartzman’s character (that is, the actor playing Augie Steenbeck), an actor having a gay affair with Edward Norton’s playwright, at one point comes to Adrien Brody’s (in a winning turn as a womanizing theater director) desperate to understand the meaning of the play. Which is, of course, a thinly-veiled ploy to try to understand the meaning of life.

“I still don’t understand the play,” Schwartman’s character says. “Isn’t there supposed to be some kind of an answer out there in the cosmic wilderness?”

“Doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story. You’re doing him right,” Brody’s urges.

There are so many times in this movie when Anderson undercuts his own eloquence with deadpan, pitter-patter line reads, but this one lands. It lands mostly because it makes me wish he’d taken his own advice. Just keep telling the story. Why do you keep breaking in? To ponder the meaning of art?

There are many people in my life who hate Wes Anderson, and I don’t think they’re entirely wrong. When I turned the movie on, my wife, laying next to me, asked “Is this the same director as that train movie?” (She was an unwilling participant in my last attempt to watch and rank all of Wes Anderson’s movies).

“Yep,” I said.

“Ugh, I can tell,” she said, rolling over to watch The Mindy Project on her phone.

Anderson’s style is instantly recognizable, and sort of overly precious and obnoxious on the face of it. And yet every time I think he’s finally made a movie I can wholeheartedly hate, he almost always delivers an ending making that impossible (I also have a theory that a certain level of liberal arts education leaves you helpless in the face of Wes Anderson’s bullshit). Even in Moonrise Kingdom, even in Grand Budapest Hotel (which I like more and more since it inspired me to read Stefan Zweig’s unforgettable memoir that partly inspired it).

Endings remain the hardest part of a film to nail, but Anderson always seems to have a stirring coda in one of his presumably numerous tweed pockets. Asteroid City is one of his first that left me thinking “wait that’s it?”

Why did we need this extra layer of artifice, allowing the creator to gaze at his navel alongside his characters? How does it help to acknowledge that this is just a play, fictional and nonexistent? The television documentary conceit (his twee twist on the mockumentary format that encompasses virtually all network comedies since The Office) simultaneously belabors Anderson’s points and distracts from them.

As Brody titled his curiously short review, “In Wes Anderson’s ‘Asteroid City,’ The Artist Is Present.”

My question is, did we really need him constantly ringing the doorbell to know he was there?

I agree with your WAIFE, I find Anderson too twee by half and generally don't like his stuff. I will not watch this!

*Fart* Gotta go!

First time I have not liked a Wes Anderson film. It did just enough for me not to hate it, I tried very hard to find the good parts as I was watching it. Your review helped me identify a few of the reasons I was disappointed by the whole movie. Guess WA can’t win them all.