The Times They Aren't A-Changin'

'A Complete Unknown' presupposes the existence of a biopic extended universe, with Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Elvis, and all of your faves.

Welcome to The #Content Report, a newsletter by Vince Mancini. I’ve been writing about movies, culture, and food since I started FilmDrunk in 2007. Now I’m delivering it straight to you, with none of the autoplay videos, takeover ads, or chumboxes of the ad-ruined internet. Support my work and help me bring back the cool internet by subscribing, sharing, commenting, and keeping it real.

—

It’s been 20 years since Jamie Foxx won a Best Actor Oscar for playing Ray Charles in Ray — followed quickly by a Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon nomination and win for Walk the Line the next year — and the musician biopic has been big business ever since. Neither a devastating parody (Walk Hard, in 2007) nor a non-biopic biopic better than any biopic ever made (Inside Llewyn Davis, 2013) could dent Hollywood’s enthusiasm for the jukebox prestige picture.

I love watching a famous song come together onscreen as much as the next person (genuinely), but after so many years of this, it’s impossible for me not to think of these kinds of movies first and foremost as complex rights deals. You can’t make a musician biopic without that musician’s songs, and that requires the permission of whoever owns the rights, plus that musician or their estate, and then there’s life rights, book deals, and God knows what else. In any case, there’s always a lot of lawyering before you even get to creative concerns.

So these days when I go see a musician biopic, I’m probably asking for a little more than just a competently made, suitably reverent origin story for some hero of the pop charts. We’ve all seen that before. I’m also asking, in some way, did this movie actually need to be made for any genuine artistic reasons — outside of the obvious commercial ones that necessitated culminating a complex rights deal? Was there actually a story here, beyond whatever they jerry rigged to match the song catalogue? Is the celebrity actor’s impression of the star worth watching? Do I need to be there or could I just listen to the music at home?

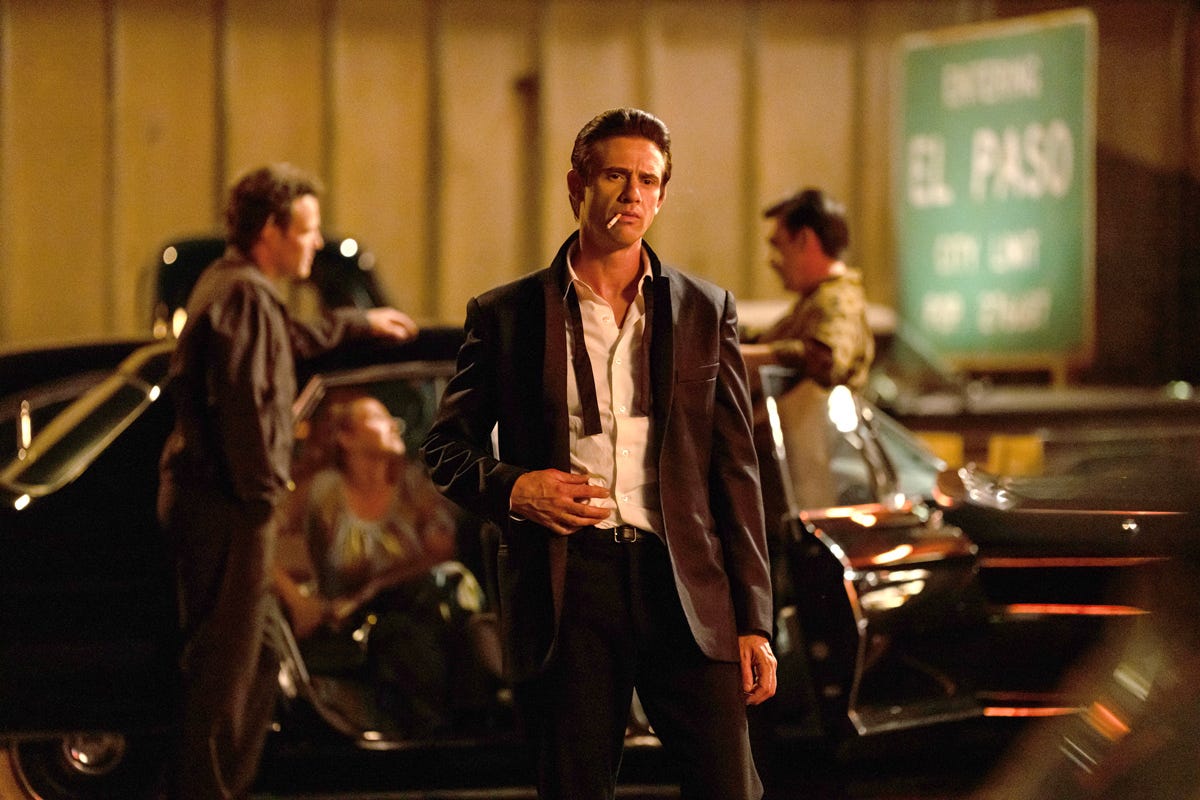

In the case of A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothee Chalamet, the answers are… mixed. It’s shot well and acted beautifully (by Chalamet, but also Edward Norton, Scoot McNairy, Monica Barbaro, and Elle Fanning), but possibly the most interesting thing about it is that it imagines a sort of biopic expanded universe, where Johnny Cash (played by Boyd Holbrook) shows up at pivotal moments to give Bob Dylan the courage to stand up for his artistic convictions. Certainly the two were pen pals and mutual admirers in real life, but how much did reality inspire this storyline and how much was it just director James Mangold (who directed both Walk The Line and this one) staging a crossover event between his two movies? Is Johnny Cash the Captain America of the expanded mid-century American musician biopic universe? (Clean. Rad. Powerful).

I enjoy plenty of Bob Dylan songs, but as a character I always thought of him as basically the ur-fuckboy. Which is to say, the original, possibly defining example of a guy who uses artistic pretensions (or in Dylan’s case, genuine talent) and a facade of personal sensitivity to disguise an inherently unreliable and se character (and score lots of babes). I was worried that an authorized biopic like A Complete Unknown would elide this aspect of Dylan and treat him like a genuine prophet, but to its credit, the fuckboyness seems front and center. “What do you want to be?” an elevator operator asks Bob in one of the trailer moments.

“I dunno… whatever they don’t want me to be.”

He’s a guy who just doesn’t want to be tied down, maaan! This extends to both his music and his relationships. It’s a paean to personal freedom wrapped up in an ode to the mid-1960s, as a time when personal freedom truly took its place as The Thing.

A Complete Unknown, based on the book Dylan Goes Electric! by Elijah Wald, is essentially built around Bob Dylan’s performance, with a full electric backing band, at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. It opens with Vagabond Dylan, with his wild frizzy hair and woolen layers, making a pilgrimage from Minnesota to the East Coast to be at the bedside of his recently hospitalized hero, Woody Guthrie, played by Scoot McNairy. Guthrie, non-verbal with Huntington’s Disease (though the diagnosis is never mentioned in the film) communicates through grunts and gestures, with the help of his friend, Pete Seeger, played by Edward Norton. Dylan pulls out his guitar and plays them a song he wrote for Guthrie, and Guthrie and Seeger both seem to realize immediately: “this kid’s got it.”

Being able to imitate a voice and style like Dylan’s in a way that’s credibly Dylan-like but not an obnoxious costume party impression is a delicate dance, and Chalamet mostly manages it. His depiction tends to be at its worst the more obviously you can feel him copying Dylan’s tics and mannerisms (that distinctive nasal whine) and best when he simply sings it straight, letting the words and music speak for themselves. They’re transporting enough in their own right, and that’s sort of folk music in a nutshell: an attempt to achieve timelessness through simplicity and purity of vision.

Seeger, a gentle old lefty who lives in a rustic cabin house with his Japanese wife and a brood of children, becomes Dylan’s sherpa through the folk world, introducing Dylan at shows, and eventually getting him a recording contract. The suits at the record company have Dylan release a debut album covering folk standards, since That’s The Way It’s Done. Dylan the songwriter is none too thrilled about it, but goes along to get along, at least at first.

Meanwhile, he meets and eventually moves in with Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning) an earnest college activist who volunteers with CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality, who organized the freedom rides), and bangs around the burgeoning folk scene. When Sylvie (apparently a fictionalized take on Dylan’s “longtime muse” Suze Rotolo) leaves for an entire summer on an organizing trip, Bobby D falls into bed with fellow folkie Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro). Dylan and Baez’s relationship is even more complicated than Dylan and Sylvie’s, on account of Baez is the more famous one (she’s on the cover of Time Magazine!) who takes to covering Dylan’s songs before they’ve even been released. Which is either a favor to him or taking advantage, depending on your perspective.

Both Fanning and Barbaro are fantastic, and Baez is probably the most interesting character in A Complete Unknown outside of Dylan. She’s alternately fascinated by him and sees through his shtick — which consists of saying spooky things and constantly negging her. In an early scene in which he goes on after her at a show, he keeps telling the crowd how pretty she is, going on for too long and adding “almost too pretty.”

After they sleep together, he criticizes her overly flowery writing, describing her songs as “like an oil painting in a motel room.”

“You’re kind of an asshole, Bob,” she responds, dispassionately.

She also attempts to puncture his self-mythologizing, asking where he actually learned music, never believing his story of learning songs from “traveling cowboy singers” while working at a carnival. She knows he’s full of shit, but he’s still too elusive to ever pin down, even for her.

A Complete Unknown probably deserves some credit for depicting Dylan’s tendency to speak in cryptic riddles as more of a troll or a personal branding exercise than falsely elevating him as some kind of oracle like so much Dylan hagiography does. And yet the biopic format is still, to some extent, inherently hagiographic.

The main conflict of the film is, of course, between the old folkies, who want to fit Dylan into the folk box of acoustic singer-songwriters, and Dylan, who chafes against their rigid conventions and increasingly experiments with electric music and rock n roll. Even his mentor Seeger seems to disapprove of this new direction, leaving Dylan’s new pen pal Johnny Cash as his only supporter. Hours before his performance at the Newport Folk Festival with the organizers threatening to pull the plug, it seems like everyone is against Bob Dylan. That is, until a drunk Cash (played wonderfully by Holbrook) stumbles out of his hotel room, crashes his Cadillac into a parked car and offers Dylan a Bugle Snack. I note this part only because I was eating Bugle Snacks myself at the time (my favorite alternative to popcorn) and I didn’t know they existed in 1965.

With Johnny Cash’s support, Dylan indeed plays electric, and the epilogue text leads us to believe that he was validated by history, as his next few electric albums ended up being “some of the most successful and critically acclaimed of his career.” As I was leaving the theater, I overheard some boomers excitedly praising the film. “That’s true, he changed all the music,” a man said to his companions. “Just like Elvis.”

It all left me a little cold. What was the take here, beyond me and Dylan’s boomer admirers both leaving feeling like we’d been told what we already believed (that Dylan was the original fuckboy who also changed music forever)? He was important because he sold a lot of records? Paul Revere and the Raiders sold a lot of records.

There seemed to be an opportunity here for so much more. My favorite Bob Dylan moment from a film actually comes at the end of Inside Llewyn Davis. The title character, played by Oscar Isaac, has just finished putting his whole heart into a performance of “Fare Thee Well” (and the movie wouldn’t work if Oscar Isaac wasn’t such a fantastic performer) and as he’s chatting with his friend played by Max Casella, we see Bob Dylan in the background, breaking into “Farewell.” Even in two or three bars, it sounds unmistakably revelatory.

It’s an important cameo, because Inside Llewyn Davis is a film about unfulfillment, and doing art because you have to even when it only ever seems to kick you in the teeth. Dylan showing up to make it work just as Llewyn has all but given up crystallizes the sort of cosmic arbitrariness of artistic success. Sometimes it’s just your moment, and sometimes it isn’t. Dylan is suddenly there, making it all look effortless in front of Llewyn Davis, who has just finished making it all look so hard. Sometimes it do be like that.

With that partly in mind, there are moments of A Complete Unknown where I kept wanting it to be a grander gesture than it is, even when it almost gets there. Whenever movie Dylan sings “The Times They Are A-Changin,’” (and it’s more than once) with its lines about an old order crumbling (“your old road is rapidly aging,” and so forth), I couldn’t help thinking about how nice it must’ve been to live in a time when that actually rang true. That seems to be the appeal of a Bob Dylan movie set in 1965 more than anything — the vicarious thrill of witnessing a true changing of the guard, a sense that the old ways were dying and something was replacing them, in a way felt by all. Dylan’s relevance is that he was so good at narrating the moment.