Larry Charles Opens Up About Borat, Bruno, and Sacha Baron Cohen

It's nice to learn that at least one person involved with 'Borat' doesn't suck.

Welcome to The #Content Report, a newsletter by Vince Mancini. I’ve been writing about movies, culture, and food since the late aughts. Now I’m delivering it straight to you, with none of the autoplay videos, takeover ads, or chumboxes of the ad-ruined internet. Support my work and help me bring back the cool internet by subscribing, sharing, commenting, and keeping it real.

—

Long-time listeners of the Frotcast will be, by now, aware of a long-standing bit whereby whenever a speaker extemporaneously refers to “my wife” in conversation, the peanut gallery responds with an exaggerated “mah wahfe” in a Borat voice as a sort of call-and-response. Mostly it’s just a dumb thing we do, that I probably shouldn’t explain, but as long as we’re on the subject, it was mostly a deliberately-dumb joke about guys of our generation over-quoting Borat.

Inasmuch as joking about people quoting Borat too much works, I think we were also mostly clowning ourselves, in that we all genuinely loved Borat — both the Da Ali G show character who predated the Borat movie, and the actual Borat movie. For me, Borat, along with probably Jackass, is one of only a small handful of genuinely transcendent cultural contributions of the 21st century (I was about to say American cultural contributions, though Sacha Baron Cohen is of course British and Borat first showed up on British television).

Borat director Larry Charles was on Chapo Trap House recently, promoting his new memoir, Comedy Samurai, and he offered some interesting insights on Borat, Bruno, and on Baron Cohen.

I hadn’t been entirely sure what to make of Larry Charles over the years. He’s kind of like comedy’s Forrest Gump (which seems to be a big thrust of the memoir, which I bought immediately), but as an individual he was always a bit of a question mark. He’s worked on or near basically every major comedy thing and person of the last 40 years, from directing Borat and Bruno to Religulous with Bill Maher, and writing on Seinfeld, Curb, and a million other things. A lot of the people he’s worked with have gone onto become canceled (like Russell Brand, who played God in a movie Charles directed in 2016) or just hated, like staunch genocide cheerleaders Jerry Seinfeld and Bill Maher. Sacha Baron Cohen hasn’t been as loud about it as the other two, but seems to at least lean that direction, albeit in quieter ways.

Having worked with so many famous comedians who either always were or have increasingly turned into assholes over the years, I did wonder about Larry Charles himself, who has so often been a more behind-the-scenes guy. So it was refreshing to discover from the interview that age, wealth (I assume), and a reasonably comfortable position in show business apparently haven’t turned Larry Charles into an apologist for the status quo (or worse, a guy who bitches about college kids being too politically correct now or whatever). It was immensely refreshing to hear him essentially say that yes, Bill Maher is kind of an asshole these days.

In fact, I thought Charles’ thoughts on Borat, Bruno, and Sacha Baron Cohen more generally were interesting enough that, with all due respect to the Chapo guys for scoring the interview, I felt compelled to do what I do and blog about it.

CHARLES:

“With Sacha, I loved Sacha really, and I felt as close to Sacha as I felt to anybody creatively, and in the situation that we were in on Borat, it really was kind of like, again, the Samurai idea of life-and-death stakes to the comedy. I was prepared to die for Sacha because we were in situations where violence and mayhem were really always a possibility. And I was prepared mentally to just step in there and save him and protect him at any cost, even at the cost of my own safety. So we couldn't have been any closer.

“And that vibe comes through in the movie, the exhilaration of feeling those kind of feelings. Of course, success breeds camaraderie as well. By the time we got to Bruno, the fact that it was such a flamboyantly gay character changed every interaction we had with the world. Everybody felt, instead of being patient with a Kazakhstani, which they knew nothing about, even though he was a rapist and an Anti-Semite and incestuous and all these things, people were still patient with him. That kind of allowed the scenes to unfurl the way they did. On Bruno, it was much more difficult. People felt immediately hostile to him, immediately felt okay getting violent with him and jostling him, and slapping him and threatening him.

“There were guns involved, and it got much more intense and it led to more conflict with us as well, like how that story should be told. I thought it was a more radical movie in a very good way, because it did show a dark, hateful version of America that I thought was really unique for a comedy. And it's also super funny, but it's amazing how almost everybody in the world has seen Borat, but when I go around the world, so many of those same people have never ever seen Bruno. And I think the reason is because it was this gay character.”

Charles smartly gets to the root of the distinction between Borat and Bruno. Aside from his point about maybe audiences in some places being less willing to accept a gay character like Bruno (who was also also sort of a bitchy, imperious fashionista, as opposed to a chummy fella like Borat), the basic difference between the movies is that where Borat, not always but often, tended to reveal the depths of its bystanders’ patience and hospitality, Bruno tended to reveal its bystanders’ shallow awfulness. The scene with stage parents immediately offering up their toddlers to lose 20 pounds or be stung by bees always stands out in my mind:

In some ways I liked that about Bruno, that most of the people being pranked really seemed to deserve it. But it makes sense that a movie that reveals people at their worst wouldn’t be as popular as one that reveals them at their most forgiving.

“By the time he got to The Dictator, Sacha's whole world had changed, really. He had become a gigantic star. He had been married and had a couple of kids by then, and he had started surrounding himself with much more of a show business entourage.

“And in doing so, I think, and in doing a scripted movie, I think he kind of lost the killer instinct that he had on Bruno and Borat. And now he's playing a role and he had to learn his lines and he had to practice the accent. With Borat and Bruno. He really had just absorbed and incorporated those characters inside of him, so that he knew what Borat's underwear should be like and his socks and what he carried in his pocket. But with the dictator Aladeen, he never really had time, but also never really spent the time to understand that character.

Instead he was getting very distracted by all the miscellaneous things that you have to take care of in a movie that weren't nearly as important as getting his character together, which was the key to the success of that movie. He'd be worried about the flag color or the uniform and things like that and it was very hard to bring him back to that place to focus. He also started to rely on a lot of outside influences who gave him very contradictory advice and not the kind of advice that he needed to make the movie as great as it could be, I felt. And he just threw a lot of people at every problem and often purposely created conflict in every situation. And all of this to me was distraction from making a great movie. And it was very disheartening to see that process take place.”

It’s an interesting answer to me, because in spending the better part of the last 20 years talking to creatives and actors and movie people, the one thing you can almost never get out of them is a bad word about people they’ve worked with in the past. Which is understandable, in that it’s bad for business. What was that thing Tina Fey told Bowen Yang? “Authenticity is expensive.”

True! —To the point that I often have second thoughts about highlighting the kind of authenticity I tend to enjoy, solely out of the fear of drawing the wrong kinds of eyeballs to it. This even though writing about things I enjoy is most of my reason for existing. (I beg you, don’t show these quotes to anyone who sucks).

Anyway, rather than just dumping on Sacha Baron Cohen (which I don’t think Charles is doing here) or “throwing him under the bus” in a self-serving way (which I don’t think he’s doing either), Charles gives a thoroughly honest, nuanced answer about the challenges of comedy and how fame can change the equation. He takes the time to examine Cohen’s motivations and acknowledge his natural desire to live an easier life. It’s much easier to imagine that than doing most of the stuff Baron Cohen used to do just for a laugh. Who wants to get rocks thrown at them and risk getting shot at? Of course, that was also part of what made it compelling. How do you not appreciate someone willing to do that?

It’d also be easy to take that quote and boil it down to “success going to someone’s head,” but that doesn’t seem to be what Charles is trying to say here either.

“You mentioned Marlon Brando before, and to me, Sacha, actually, in the same way Marlon Brando introduced a new form of acting, Sacha should’ve won an Oscar for Borat.”

“Because nobody has done a performance like Borat, where he is Borat 16 hours a day, six days a week, without breaking, in front of real people and creating an illusion that is so real that people didn't question it. That is the ultimate illusion of acting, and he didn't get credit for that, really.

“I mean, people loved him and loved the movie, but as an acting exercise that was unprecedented. And I think over a course of time, rather than kind of honing in on that, the way Andy Kaufman might have, I think if he had lived, I think that Sacha didn't want the pressure anymore. He didn't want to be frightened every time he went into a scene that he was going to be hurt. I don't think he wanted to go through that again and refused to do a Borat sequel at that time. I think that he wanted a kind of easier way to make a living, and I think being a Hollywood star was a lot easier than being Sacha, the guy who did Borat. And I think he moved in that direction. I think artistically that hurt him and also compromised his views, which had been very sharp and singular, and then suddenly was not quite as special. He took the edge off his own comedy sensibility in a way.”

I think Larry Charles is exactly right here. People in my generation seem to do a lot of hand-wringing about Borat, like they’ve taken to heart criticisms that the movie and the character were always mean-spirited, if not downright xenophobic and Islamophobic and misogynistic and whatever else, and that we should feel bad for having ever laughed at it. As if we’re so much better and more virtuous now (or that we should only feel good laughing at overtly virtuous things).

Kazakhstan certainly took it on the chin being the butt of that joke, but it was always based more on British/Americans’ ignorant assumptions about some place that was just some exotic “other” to them than it was about the place itself. And I don’t think anyone halfway intelligent came away thinking anything less about Kazakhs because we laughed at Borat (though of course I can imagine it feeling that way at the time if you were actually from Central Asia). Certainly not everyone who saw Borat and laughed at it was halfway intelligent, but at some point we have to defend the artist and comedian’s right not to have to tailor every single movie or joke to the dumbest person in the audience. Maybe that would be safer, but boy would it suck.

Some of the jokes were lower-hanging fruit, but for the most part their hearts seemed to be in the right place — letting us laugh at all the absurdities of the War on Terror that just seemed so inescapable and so oppressive at the time. I don’t know that we all expected jokes to change the world in 2006, we just wanted to feel less insane.

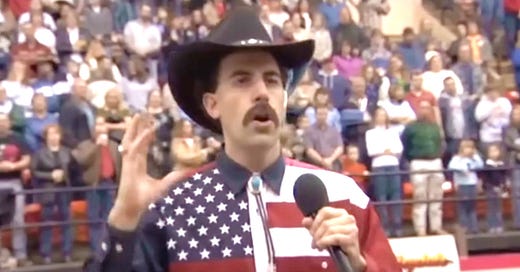

One of my favorite jokes in Borat is when he’s at the rodeo some place down south, and the announcer asks Borat, “You’re not one a these dad gum moslems, are ye?”

And Borat, looking slightly alarmed, says “No, I am Kazakh. I follow the hawk!”

That’s a great joke, and it’s one, I think, that exposed the absurd xenophobia of that moment rather than it perpetuated it. That you could befriend a “nice eye-talian” who worships hawks as long as he didn’t own a Koran.

Obviously, it didn’t change the world and cure racism and make flowers bloom in darkness. It didn’t keep us from starting a new war with Iran barely 15 years later or from helping Israel do ethnic cleansing. But I tend to think that’s expecting too much from comedy. The best it can really do is to make you feel like you’re not alone and to momentarily forget that you’re going to die someday.

I don’t think it’s any more of a gotcha to point out that some of the Borat people became genocide cheerleaders than it is exonerating to point out that some of them, like Larry Charles, didn’t. It’s nice to know that being successful and comfortable doesn’t have to turn you into an asshole. It’s comforting to hear someone who makes you feel less insane in a world that otherwise seems firmly dedicated to driving you crazy. That might not change the world, but it can certainly make it feel more livable.

Very well said, Vince, and thanks for writing this up—I don't think I'd have seen it otherwise. It's good that people like Charles are still articulating nuanced views rather than Hot Takes. How refreshing.

Man, I'd never really put together how people were nice to Borat, but immediately mean to Bruno.

Almost like foreshadowing, in a way.

Somehow I assumed Baron Cohen's IDF character from "Who Is America?" made it so he'd be a bit more aware of what was going on rn buuuuut guess not.

(Also, my PFP was a shitty picture of Borat since like 2006 on a billion places, Uproxx included.)