Welcome to The #Content Report, a newsletter by Vince Mancini. I’ve been writing about movies, culture, and food since I started FilmDrunk in 2007. Now I’m delivering it straight to you, with none of the autoplay videos, takeover ads, or chumboxes of the ad-ruined internet. Support my work and help me bring back the cool internet by subscribing, sharing, commenting, and keeping it real.

—

It’s never a great sign when you leave a movie asking yourself, “Why did I want to see this again?”

It’s not that Saturday Night, a movie about the rush to get the first SNL on the air in 1975, is dull or dumb or tough to sit through, mostly it just feels incomplete. Unfocused. Missing that special something. Something about it feels like an extended trailer for a movie that never quite happens. As the credits rolled, just as the story reached the first SNL making it to air, I sat there wondering what exactly it was that I had expected in the first place.

While I haven’t watched for a few seasons now (not for any particular reason) I guess I’m something of an SNL completist. I read the oral history, read the Caddyshack book, watched A Futile and Stupid Gesture… and so when this new SNL movie directed by Jason Reitman came out, a story that takes place entirely during the one hour before air time of the first SNL broadcast, I guess I figured, “Why not?” Might as well, I’ve come this far already."

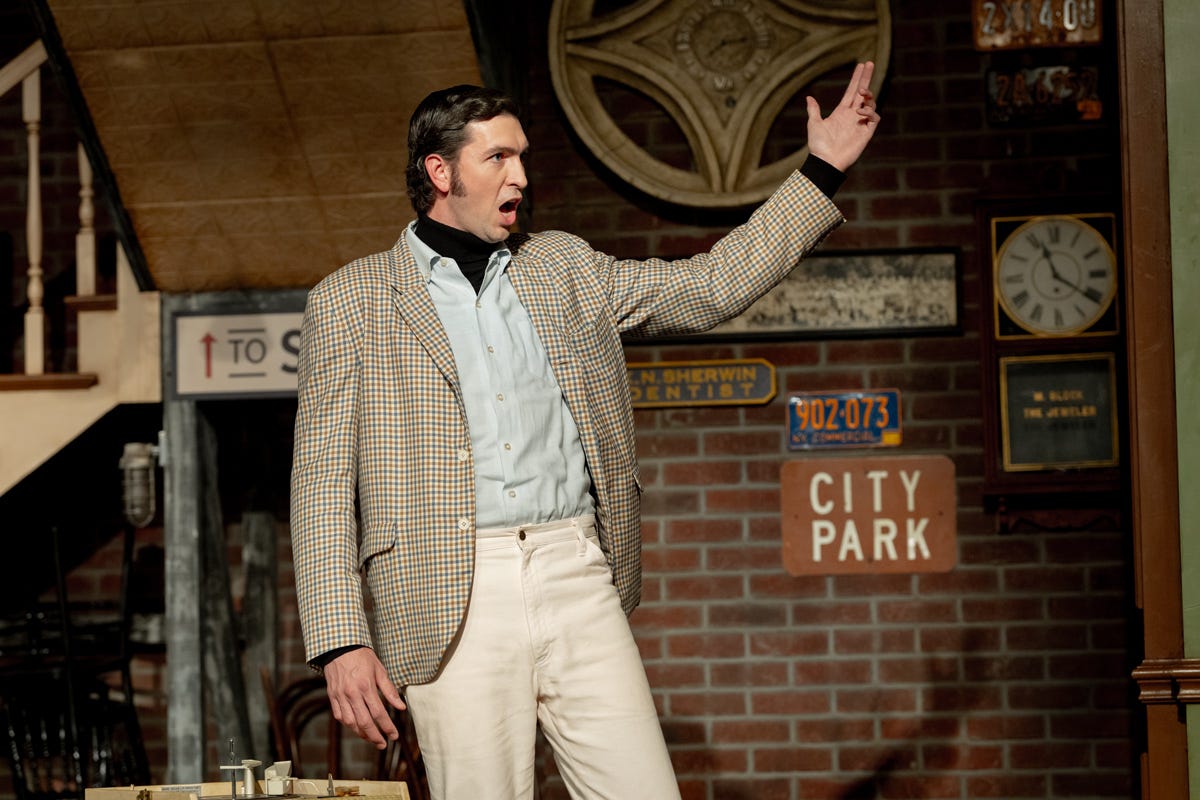

Gabriel Labelle, last seen as young Spielberg in The Fabelmans, plays Young Lorne Michaels in Saturday Night. As we open the film, he’s running himself ragged trying to get his counter-culture comedy show off the ground and onto the air. Some of his biggest problems include: his wife, Rosie (Rachel Sennott) having an affair with Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi (Matt Wood) refusing to sign his contract and generally being a drug-addled prima donna, host George Carlin (Matthew Rhys) also being a drug-addled pain in the ass, Chevy Chase (Cory Micael Smith) starting to get a big head, and a host of other flaky performer-related issues, not to mention a network frenemy (Dick Ebersol, played by Cooper Hoffman) constantly pushing him to cut costs and a network exec (Dave Tebet, played by Willem Dafoe) who may have greenlit this entire fiasco entirely for leverage in a contract dispute with Johnny Carson, partly under the assumption that it would fail.

Phew, that’s a lot of problems to solve! And in order to reconcile them all in 109 minutes, the performers have to talk fast! The pacing is part of the story’s conceit, and so there’s a familiar, formalistic slickness to Saturday Night’s construction — constant tracking shots, lots of walk-and-talks, characters encountering each other while traveling through corridors, all while a jazzy soundtracks bops it along, Soderberghianly.

The script, by Reitman and Gil Kenan (the two having previously collaborated on the nü-Ghostbusters movies) takes problems that Lorne Michaels would face over the course of the first season — Chevy’s ego, Belushi’s drugs, Garrett Morris feeling like an outsider, the female performers not getting their due, Jim Henson being a gentle hippie, Micheal O’Donoghue being a smug prick, etc. — and squishes them into this one hour before air, bookended by constantly ticking clocks, producers screaming “45 minutes to air!” “30 minutes to air!” and so forth. (Nicholas Braun from Succession, by the way, plays both Jim Henson and Andy Kaufman).

We don’t really believe that Garrett Morris (played by Lamorne Morris, no relation) spent the entire hour before air wandering around wondering “who am I?” like Derek Zoolander, or that John Belushi was laying on the ice in Rockefeller Center staring up at the stars with only minutes before air, but we’re meant to accept this artificial condensing of future problems as part of the film’s dramatic license. Which is… fine, I suppose, only it cuts against the entire rush rush rush, tick-tock tick-tock structure of the film. Is this meant to be like a heist film or isn’t it? And if I can accept these two transparent, competing conceits, what do I get out of it?

They say the worst possible reason to include something in narrative non-fiction is “because it really happened,” and Saturday Night seems to suffer from the checklist problem. It’s constantly going “and this happened! and then this happened! and also this happened! …isn’t that crazy?” which isn’t the greatest way to tell a story. Not to mention that a lot of this stuff obviously didn’t happen, at least not in the time frame presented. We’re meant to pretend that all this stuff happened, just to make it seem more dramatic. And if we’re just pretending that the time frame was the dramatic part, we’re probably missing the actually dramatic part.

Which is not to say that there aren’t aspects of SNL history that I have and continue to find fascinating. It’s hard not to shake the constant sense that the Boomers won the generational lottery. Stories about the SNL/National Lampoon’s/SCTV generation (of which Jason Reitman’s dad, Ivan, buddies with Dan Aykroyd and director of Stripes was part of) always seem to take the form of “we revolutionized comedy(/movies/music/TV) by tapping into youth culture!”

In these Boomer narratives, the old fuddy-duddies are always corny and old and don’t understand these hip new free thinkers, but the olds are so desperate to be relevant again and to tap into that massive youth market that people like Lorne Michaels, Warren Beatty, the makers of Easy Rider, etc. end up getting their shot, maybe a little before they were ready to (ergo, “the Not Ready For Primetime Players”). A world changed, thanks to the scruffy unlikely Boomers is always the triumphant ending, like the Ewoks dancing on logs after blowing up the Death Star.

Boomers traded on the currency of youth in ways that Gen X, Y, and millennials never really did, and now they get to resell it to us in the form of nostalgia. Incredible scam! Even if the nostalgia of it is lost on me, it’s still fascinatingly exotic. I don’t think my generation of elder millennials or the Gen X era I grew up idolizing (Sandler, Hartman, Farley, MacDonald, etc.) ever thought “these jokes are funnier because we’re young!”

The whole “Boomers discovered psychedelics and killed conformity” narrative is also tough to square with comedy in particular, which tends to have a shelf life and a had-to-be-there quality in ways that, say, music, and musician biopics, don’t. No matter how many times we see a famous song come together on film (fictional Eazy E hitting the first line of “Boyz-n-Tha-Hood,” say) it still seems to have that cathartic, carving-order-from-chaos quality to it. By contrast, some of the supposedly revolutionary comedy in Saturday Night just doesn’t quite play. The “Wolverines” sketch that opens the very first SNL, for instance, might as well be in Chinese.

What is the context of this sketch? A guy comes home to a language class in his parlor? And it’s about wolverines? And then the button is them dying?

Saturday Night recreates the sketch, and it’s depicted as a triumphant moment (which seems like a fair read, you can hear the original studio audience laughing) only it fails to transport because the humor doesn’t really translate. The movie tricks don’t work well enough to put me in the same mind space as those studio audience members eating it up. Based on this movie, I’m left to conclude that John Belushi’s chief skill was… faking heart attacks? That can’t be right, can it?

The film also recreates Andy Kaufman doing the Mighty Mouse bit, which is much more recognizable as comedy bit, but also how many times have we seen this in film or in a show at this point? Saturday Night kind of wants credit for inventing a new structure while largely still playing the same hits.

Saturday Night does a disservice to some of the things that are genuinely interesting about the story by shoehorning them into the traditional biopic, hero’s journey format. The other day a comedian friend of mine said something about how being around comedy, you get to see how often audiences respond to aspects of performers that might actually be pathology. The movie, to its credit, never depict its characters as saints. Carlin doesn’t want to be there and doesn’t get it, Chevy Chase is an ego maniac, Aykroyd is kind of a lecherous spectrumy horn dog, and Belushi is basically a farm animal. They’re pretentious and passionate and young.

Yet there’s a compelling duality to Cory Michael Smith’s performance as Chevy Chase that’s missing from some of the other characters, probably because we actually get to see him being funny in addition to being an asshole. And maybe part of the reason he’s funny is precisely because he’s such an asshole. This, to me, is much more interesting than Lorne Michaels ultimately getting the trains to run on time.

While it’s structured as a sort of counter-culture-pulls-it-off story, Saturday Night’s most interesting characters invariably end up being the old guys. Willem Dafoe’s performance as Tebet, alternative puffing Michaels’ ego even when Tebet doesn’t entirely believe in him, and then ultimately seeing something in this show that makes him greenlight it, is a more interesting journey than Lorne Michaels’. JK Simmons steals the show as Milton Berle, a bitter, horny old hater who tries to steal Chevy Chase’s fiancee, partly by just whipping out his famously enormous dick. When Chase tries to body him with roast jokes about being a has-been, Berle quips, “Kid, if you want my comeback you’ll have to scrape it off the back of your mom’s teeth.” (Comeback, cum back, that’s wordplay, kid).